FEATURES – ‘Berries to Beads’ by Daphne Boyer

[ad_1]

If there’s any respite to be found from the tough moments that appear to be to surround us, it’s in artwork. Art that is relocating and beautiful, intriguing and awe-inspiring, and demonstrates life in the most earnest way. I discover this to be true in the get the job done of Daphne Boyer, a visual artist and plant scientist of Red River Métis descent.

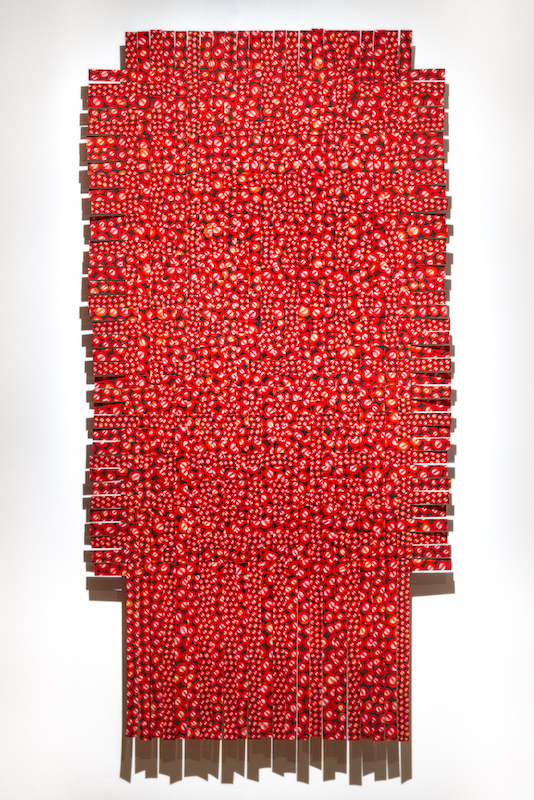

Utilizing superior resolution images of various berries and plant materials (or porcupine quills) as electronic beads—what she phone calls the “Berries to Beads” technique—Boyer generates vibrant performs that fork out homage to conventional handwork, celebrate her Indigenous heritage, and honour the life of her kin. The electronic nature of her perform lets her to, in her phrases, “scale up, scale down, play with it, and make massive stories about compact original will work.”

With ancestors who were being founding members of the very first Métis country in Crimson River (found in Manitoba), Boyer is poised to notify the tales of her heritage. Boyer’s mother, an archivist and storyteller of Métis ancestry, retained vital documents and stood up to her Catholic French relatives who were being in denial of their Métis ancestry. Describing her mom as a robust girl and fantastic spirit who was way in advance of her periods, Boyer adds that she “opened the door for [her] era to assert this component of our ancestry, which was truly lovely.”

Escalating up, Boyer picked berries and offered them to area physicians to pay out for Woman Guidebook camp, and recognized that she preferred to be an artist. She enrolled in textile layout in an art university but learned that the substances created her quite sick. “As a to some degree unhappy 2nd alternative, my spouse and I finished up restoring a large backyard that was initially planted by [Evelyn Lambart,] the initially female movie animator at the Nationwide Film Board,” Boyer shares. They spent 11 decades restoring that yard, and in that atmosphere Boyer identified herself overwhelmed with a will need to convey herself. Her spouse built a studio for Boyer to experiment with distinctive components, to figure out what she could work with. In a ski-doo accommodate and boots, with the windows open up large to wintry air, she established she could operate with acrylic paint, plant product, and a camera, which now type the foundation of her artwork.

With no formal instruction, self-doubt crept in but was promptly extinguished by her supportive spouse and a number of effective grant purposes. Considering that 2017, Boyer has taken on her art entire time, doing work with a staff composed of Barry Muise, Lina Samoukova, and Etienne Capacchione. With each other they designed Boyer’s signature “Berries to Beads” strategy, but it wasn’t devoid of some trial and mistake. Experimenting with how to use actual berries as bodily beads did not pan out so very well. “That total summer months, working tricky, [we] finished up with a mound of jam and big disappointment,” suggests Boyer. “And I just, I was devastated. I’d put in my grant funds and then came this flash… Properly, I can do this photographically.”

In Victorian situations, when there was result in to regenerate misplaced things in art, Métis women turned learn beaders of floral layouts, which Métis men wore when they travelled and transported items. Boyer states “they would travel in between Indigenous communities, from 1 to the other,” them and their dogs in elaborately beaded clothing. “It was like you could listen to them coming from miles away with these canine and the jingles and the colour and the snow, when they would get there into the fort in a impressive show.” What had been just scatterings of seeds impressed blooming beadwork, which distribute across the nation as cultural emblems.

Seeking to master additional about how her relatives fit into the history of Métis men and women in the Pink River district, Boyer met Dr. Maureen Matthews, Curator of Ethnology at the Manitoba Museum, who confirmed her a range of artifacts—one remaining “Moss Bag H4-2-13,” designed by an mysterious Métis-Dene artist. This artifact was a baby provider that was adorned with a spectacular array of floral beadwork, with the Métis infinity indication embedded in a rose on the ideal of the style and design. Boyer was so taken by this artifact that she recreated an 8-ft-very long edition working with her “Berries to Beads” method.

“It is imagined that these girls had adopted the tactics, these floral patterns, but they also embedded in individuals floral styles bits of their possess religious beliefs, and also the resistance to colonization,” says Boyer. “And it is imagined that this sort of thorny stem displays in a pretty refined way, a rejection of colonization and that the rosebuds genuinely replicate the probable to bloom, that things are unfolding.”

When you search at her operate, vibrance leaps off of it—the final result of Boyer’s grit and passionate obsession with depth. The electronic berries seem as even though you could achieve your hand by means of the body and get a handful. Realism is a pure outcome of photography, but it is the arrangement that weaves meaning into the final get the job done. “I see each individual completed get the job done as raw content for the subsequent technology of get the job done,” suggests Boyer. “And in that way, I’m embedding, like DNA, I’m embedding the generationality of the stories I’m telling into the will work.”

Hemoglobin is a woven tapestry of cranberry pictures (or tiles), printed at diverse scales and stitched together. “It moves like it’s respiration,” Boyer states, as it embodies the last breath of her mother Anita, who was a lifelong yoga practitioner and died in shavasana, the corpse pose.

Applying berry tiles that allude to Hemoglobin, Barn Owl and Moon celebrates Anita’s everyday living-extended enchantment with owls, harbingers of guests. An owl glides in a sky of midnight blue berries—a unique distinction to the energetic crimson hue of Hemoglobin. It implies that Anita’s spirit now resides in the other environment, from which she sends owls to convey to her family when she’ll be browsing. “We typically listen to [the owls],” Boyer claims. “We say, there’s Mum, [and] we’ll go to the window and hear.”

The unbelievable Birthing Tent includes a substantial velvet cover, printed with a constellation of the oxytocin molecule, and from it huge silk ribbons of different patterns rain down. The ribbons stand for the babies that Boyer’s great-grandmother Éléonore, an itinerant midwife, helped beginning. The cover, hung “like a bosom,” and ribbons pull readers into a motherly embrace, and the oxytocin molecule formalizes our bond with some others. “My grandmother Clémence and also Éléonore, they weren’t cuddly females. They had been sturdy, fierce women,” Boyer shares. “And by the time I came along, my grandmother experienced lifted extra than 25 kids. And she was not interested in me. So this is a bit of a fantasy about getting held.”

It’s been frequently acknowledged that time heals all wounds, but artwork has a therapeutic ability extra potent than that felt by the slow drag of the sun across the earth. Last year in On Beaded Ground, a group present at the College of Victoria’s Legacy Art Gallery, Boyer was stunned by the result of her perform. “People came into the show, and they cried,” she says. “They stated, this get the job done is so therapeutic.” Local community engagement is an integral portion of all Boyer’s shows, as is functioning with other Indigenous artists and communities.

When asked what’s next for her, Boyer says, “Somebody interviewed me a short while ago and claimed, ‘Well, when are you going to convert this procedure about to the subsequent generation?’ I believed: Which is an assumption, that is an ageist assumption. I bought a good deal of miles still left in me, and I’m heading to melt away it up!”

Boyer’s do the job is at this time on exhibition at Fort Calgary till June 26, 2022, and will vacation immediately after to Montréal, arts interculturels (August to Oct 2022) and Remai Contemporary in Saskatoon (September 2022 to January 2023).

Find out a lot more about Daphne Boyer on her internet site and Instagram.

*

Showcased Image: Rose (2019) by Daphne Boyer, image taken by Lina Samoukova.

All photographs courtesy of Daphne Boyer.

[ad_2]

Supply url